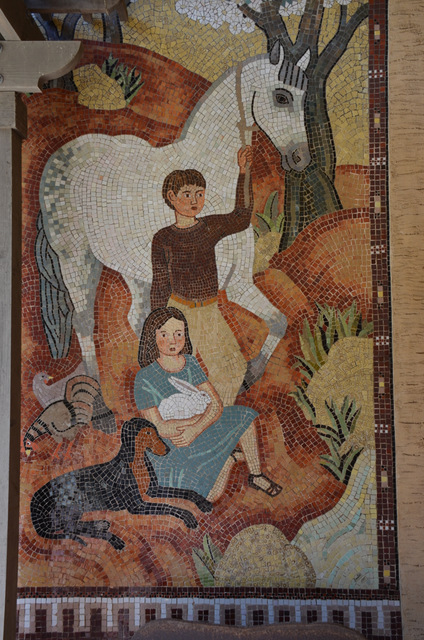

San Francisco Zoo

Mother’s Building

These murals, on the Mother’s Building at the San Francisco Zoo were WPA projects. They were done by three sisters: Esther Bruton, Helen Bruton and Margaret Bruton.

Helen Bruton has murals in downtown San Francisco that you can read about here.

Here is an excerpt explaining the sisters work on the Zoo murals in their own voices:

This Oral history interview with Helen and Margaret Bruton, 1964 Dec. 4, is from the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Interview with Helen and Margaret Bruton

Conducted by Lewis Ferbrache

In Monterey, California

December 4, 1964

LF: All right, Margaret and Helen, about the Fleishhacker Mother’s House mosaics – you were mentioning Anthony Falcier and how you learned from him.

HB: Yes, he was actually, at the time, a tile-setter in Alameda, but he was a thoroughly-trained mosaicist from his early days in the old country. He used to tell us how he came over here. He came over here to work on the courthouse in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, which evidently had a mosaic top. And then he came out to San Francisco, to join a group of Italian workmen who were doing the mosaics down at San Simeon for the Hearst Castle. Since then, we ran across another man who worked in that same crew, several in fact. In fact, I think there was one on the WPA whose name I can’t remember. But if it hadn’t been for Mr. Falcier, I don’t know what we would have done, because he gave us pointers that we would have been quite helpless without. About how to set up the drawing, how to reverse it, how to divide it in sections in such a way that when the actual mosaic was mounted on the wall – which was an operation that began from the bottom and worked up –the section that you were mounting was square enough in shape so that it didn’t sag or settle too badly at one side or another, and begin to throw the thing out of wack. Because everybody that saw us working always had the same expression. “”Oh, that’s just like working a jig-saw puzzle.’’ Well, it was a little like a jig-saw puzzle on a big scale.

LF: What were the sizes of these tiles, did you say?

HB: Well, the material that we used – as I said we couldn’t get any – there was no such thing as getting “smalti,” which is hand-cut Venetian enamel material. We used for the material some commercial tile that was manufactured at that time in San Jose, California, by a small tile outfit called Solon & Schennell, or the S&S Tile Company. They made a beautiful commercial tile, too beautiful to be very successful as commercial tile, because they couldn’t really satisfy the jobbers, who insisted on a perfect match to every lot of tile, which they had catalogued by number. There was so much variation in their tile that there was a great deal of waste from a practical commercial standpoint. And the tile that we used was mostly that tile that was what they would call a second, because of the variation. We had names for these tile colors, one was called St. Francis, and St. Francis varied in color all the way from deep Mars violet to a fawn color almost, or a strong ochre color, warm ochre, but it was the same glaze, depending on where it was put in the kiln it would come – that would be the range of shades.

LF: Different shading?

HB: Yes. And it was very, very strong, very good body to the tile, except that it was so tough that before we could even cut it up in smaller pieces, use any kind of tools on it, we had to have the thickness reduced by about half. And the way we did that was, we took it to a marble works over in Berkeley, over in Emeryville, really, on the waterfront there in the industrial section, and they would mount the tile on slabs of marble set in plaster of Paris, glazed side protected of course, with the bottom side up, and rub about half of it off. Then it would come in a workable thickness. And poor Len sawed it, used to saw it in strips of about three-quarters to an inch in width. And from then on we could cut it into any size we wanted, with some good strong tile nippers. Except that there was a difficulty in setting it up, finally because of the very absorbent terra cotta back, which drew the water out. When the cement coat was put on the back of the tile, it sucked the water out unless the terra cotta was dampened beforehand. So we always had the problem, when it came to mounting it on the wall finally, of dampening the back without making it so damp that the surface, which was eventually to be the fact of the decoration, would be still kept dry enough to hold on to the paper. And we did. It just made it a little bit more complicated in the process. But it was in the mounting that Mr. Falcier was so valuable. He’d come over with us from Alameda every day. I think it took us about almost a week for each one – five days for each panel. And he’d actually mix the concrete, the mortar. Esther was helping me on that. I don’t know where Marge was, and Len, I don’t remember Len being there. It is funny, but he must not have been with us when we were actually working with Falcier. But anyway, Mr. Falcier would mount a certain amount face out – you see the paper would still be stuck on the face – and each day we’d move up so much. We might set eight or nine pieces, depending on the way the design built up, the sections built up.

LF: You would have your cartoons to go by, I would imagine?

HB: Yes.

LF: Did all three of your get together on the selection of the subject matter, the topics? Did you talk it over between the three of you?

HB: Oh, I suppose we did.

LF: Or what it suggested by the City or –?

HB: I think it was, not – as a matter of fact, I think that particular thing was pretty much my job of designing. Somebody else, probably Esther or Margaret might have suggested the subject matter actually, but I remember it was a matter of – I remember hardly doing more than one sketch of that, especially St. Francis. I think I put it down and that was it. Of course, there was more work put on it as you got to getting it full size, but I think that first sketch, which was rather unusual for me because the more work I did the more fooling around that I do in design, and maybe not really improving it.

LF: You had to submit the design or the sketches to Dr. Heil or someone in his office?

HB: Yes, and then of course, you’d bring in a sketch and a proposal of what material was to be used.

LF: Did you estimate your time and what you needed?

HB: Oh no, you couldn’t possibly, because we’d never done such a thing before. But I don’t remember that it took, I’m afraid that I couldn’t say exactly how many months it took, whether we were two months on it, or three months, or whether – considering both the panels, we might have been perhaps three months.

LF: This was the first work done in the building?

HB: I think Helen Forbes and Dorothy Puccinelli were working at the same time. In fact, I know they were. But we were not there anything like – that project continued for a long, long time, but of course we didn’t actually have to work out there at the building until it came to installing the panels.

LF: I see. Where did you do your work then?

HB: At home in Alameda.

LF: In Alameda, that’s interesting.

HB: That was the house that we’d always lived in, and we had a wonderful big studio in the top floor, the whole top floor with great big dormer windows on three sides.

LF: And you completed the mosaic murals in the house and had them moved?

HB: They were in sections, you see. We did it on the floor. We laid it out on the floor as we completed it section by section. One thing that made this particular material still more complicated was that the color was only on the fact. So we used to have to lay it out roughly on the face so we could see what we had done, what we had before us. But, of course, when it came to mounting it, the mounting paper, the heavy paper on which it was mounted and transported, had to be put over the face. So when it was laid out on the floor, then we mounted paper over the face so it all disappeared. In other words, it was completely covered up and dismantled. And we had to get the paper off the back and clean it up so that the mortar could go directly on the back.

LF: This is the Fleishhacker Zoo Mother House? In other words, it was a sort of resting place, and so on, for mothers and their children visiting the Zoo? Is that correct?

HB: Yes. It was a memorial given by Mr. Herbert Fleishhacker, as I understand it, given in memory of his mother, Delia, because it says across the face of it, “To the memory of Delia Fleishhacker.” And I remember Mr. and Mrs. Fleishhacker came over one day to see it. They wanted to see it while it was still on the floor to see that there was not going to be anything offensive slipped in, and they had to climb three flights of stairs to get up to it, but they did it.

LF: This was when it was being installed or — ?

HB: Just before, when it was completely laid out.

LF: In your house?

HB: At home in Alameda, yes, because they wouldn’t see it again until it was all on the wall, so that was something they had to do, if they wanted to see it.

LF: I’ve never seen this because naturally a man can’t go in to see –

HB: No, but this is on the outside.

LF: It’s on the outside? I thought it was on the inside.

HB: Oh no, it’s –

LF: It doesn’t say here in the thesis where it was located so –

MB: It’s right on the outside of the building.

HB: I have a number of other photographs that will give you a better idea. That doesn’t give you an idea of the outside. (Interruption to look at photographs).

LF: You were talking about the mosaics, Miss Helen Bruton, on the outside of the Fleishhacker Zoo Mother’s Rest House. I had thought they were inside, but they are outside. They have stood up against the weather, have they?

HB: They just seem to be exactly the same as they were. That was one of the things I was interested in. The other day I looked at them hard, to see what was going on and I can’t see that there’s been any deterioration at all. Of course, they’re not actually exposed to the weather. It’s a loggia, they’re at either end of a long loggia perhaps sixty feet long, and you can turn from one to the other which makes it –

LF: You believe this was finished then probably in the late spring of 1934?

HB: Yes, yes, I would say that very definitely because I think we have a little tile with the date on it. It’s there on the panels.