It took 116 years for Fort Point to become a National Historic Site, and its life along that road was a bumpy one. Construction on Fort Point began in 1854. Thanks to the California Gold Rush, commerce was booming in San Francisco, and it was important that the portal through which valuable cargo flowed, the San Francisco Bay, was protected. The Fort, as it is configured today, is how it was originally envisioned. In 1857 a reporter for the Daily Alta California described the workmanship at Fort Point as “solid masonry of more than ordinary artistic skill which meets the eye at every point…the visitor is at a loss to determine what he admires most-the granite or the brickwork…” Once the foundation-thousands of tons of granite, brought from China-was laid, work began on the masonry arched casements that would house the guns and the troops. Originally the entire fort was to be of granite, but three years into the project the engineers decided to switch to bricks, made to their specifications on a hill just south of the fort. Master masons were hired for setting and laying the millions of bricks; they were assisted by numbers of men that had gone “bust” in the gold rush.

It took 116 years for Fort Point to become a National Historic Site, and its life along that road was a bumpy one. Construction on Fort Point began in 1854. Thanks to the California Gold Rush, commerce was booming in San Francisco, and it was important that the portal through which valuable cargo flowed, the San Francisco Bay, was protected. The Fort, as it is configured today, is how it was originally envisioned. In 1857 a reporter for the Daily Alta California described the workmanship at Fort Point as “solid masonry of more than ordinary artistic skill which meets the eye at every point…the visitor is at a loss to determine what he admires most-the granite or the brickwork…” Once the foundation-thousands of tons of granite, brought from China-was laid, work began on the masonry arched casements that would house the guns and the troops. Originally the entire fort was to be of granite, but three years into the project the engineers decided to switch to bricks, made to their specifications on a hill just south of the fort. Master masons were hired for setting and laying the millions of bricks; they were assisted by numbers of men that had gone “bust” in the gold rush.

*

*

Slow in finishing, the Fort construction was completed just in time for the outbreak of the Civil War. The military occupied the Fort and prepared it for attacks that never came. Life for those stationed there was not easy: the thick walls, built to protect the Fort, made for dark spaces; the fog, an ever present element of San Francisco made the place cold and damp. The Bay itself also took its toll on the structure. The constant waves threatened to undermine the footings. In early 1862 work began on the 1500-foot sea wall that still remains. Again, thousands of tons of granite, this time from Folsom, California, were laid down and keyed together. The spaces were filled with cement and then covered with tar-impregnated cloth and molten lead.

After the Civil War the Fort was abandoned, except for a caretaker. It did, however have a dozen men garrisoned there during the 1906 earthquake. After all the men were out safely, they noticed that the entire hillside wall had moved away from the rest of the building by eight inches. The Fort was abandoned, and plans to turn it into a detention barracks were adopted. The Fort was remodeled, and yet, never did become detention barracks. The World War I troop buildup brought the Fort back into use as housing for unmarried men. During this time the Fort was also used as a “base end station,” which located the positions of attacking ships and controlled the firing of seacoast guns, mortars, or mines to defend against them. Abandoned once again after WWI, the Fort fell into severe disrepair.

Damage caused by the 1906 earthquake: tie rods were positioned, and the wall was pulled into place and anchored back to the main structure.

Damage caused by the 1906 earthquake: tie rods were positioned, and the wall was pulled into place and anchored back to the main structure.

The interior courtyard with the original cast iron columns and capitals

The interior courtyard with the original cast iron columns and capitals

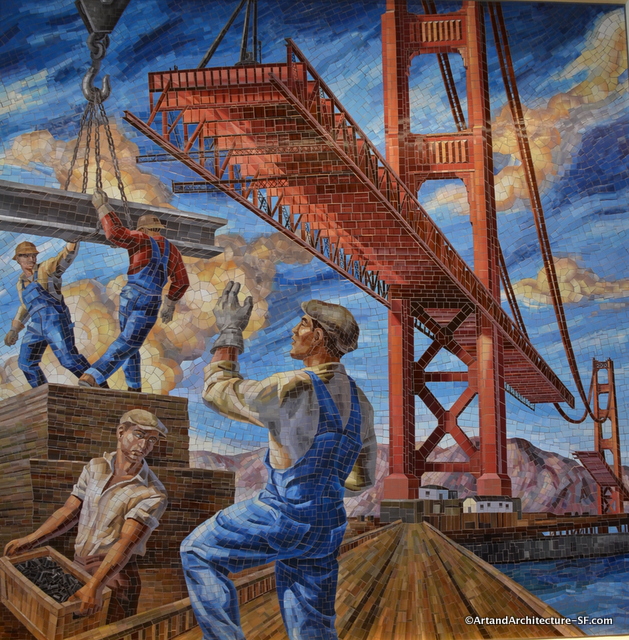

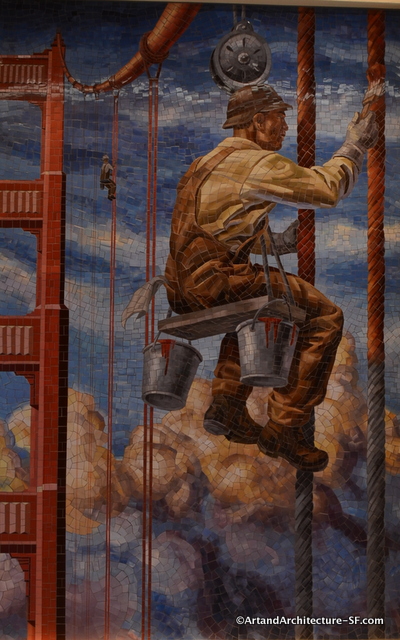

In the early 1930s funds were being raised for the new Golden Gate Bridge. Engineer and designer Joseph Strauss initially felt the Fort would be an impediment to the bridge and wanted it gone. In 1937, however, after a tour of the Fort and the realization of its superior craftsmanship, he wrote to the Golden Gate Bridge District: “While the old fort has no military value now, it remains nevertheless a fine example of the mason’s art. Many urged the razing of this venerable structure to make way for modern progress. In the writer’s view it should be preserved and restored as a national monument.”

*

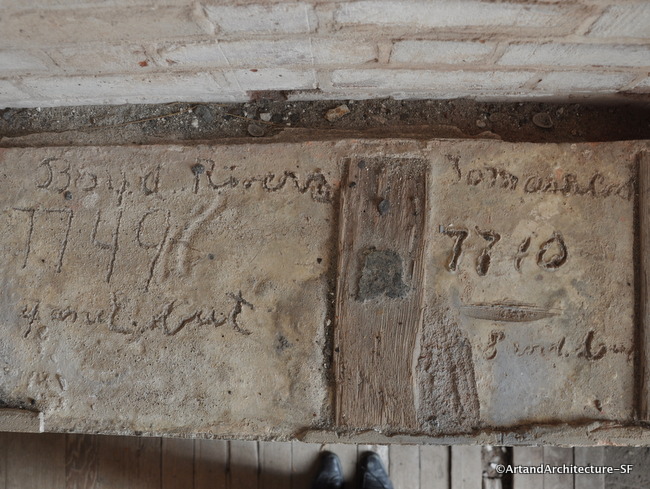

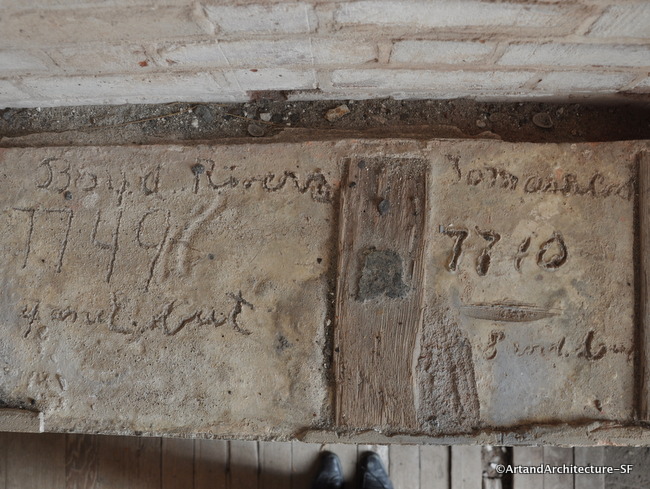

Graffiti left by prisoners from Alcatraz sent to repair Fort Point in 1914

Graffiti left by prisoners from Alcatraz sent to repair Fort Point in 1914

World War II found the Fort again refurbished and armed with Anti Motorized Torpedo Boat guns. The Bay never saw any action during the war, and the rapid demobilization after WWII left the military with a relic. Preservation enthusiasts started to organize beginning in 1947, but no government agency would step in and claim the Fort. In 1959, a group of retired military officers gathered together and formed the Fort Point Museum Association. They raised money and public awareness, and in 1970 President Richard Nixon signed a bill designating Fort Point a National Historic Site.

The Fort has four small jail cells. They now function as offices for the park rangers.

The Fort has four small jail cells. They now function as offices for the park rangers.

Prisoner art work, found on the jail-cell wall

Prisoner art work, found on the jail-cell wall

Garrison Gin, used to move cannons to the upper floors

Garrison Gin, used to move cannons to the upper floors

Fort Point is now part of the United States Park Service. It is open Friday through Sunday from 10 am to 5 pm. Candlelight tours are given in January and February. A full report of the history of the Fort, as well as its construction and restoration documentation can be found on the the National Park Service website.

Fort Point is now part of the United States Park Service. It is open Friday through Sunday from 10 am to 5 pm. Candlelight tours are given in January and February. A full report of the history of the Fort, as well as its construction and restoration documentation can be found on the the National Park Service website.