Foundry Square

1st and Howard

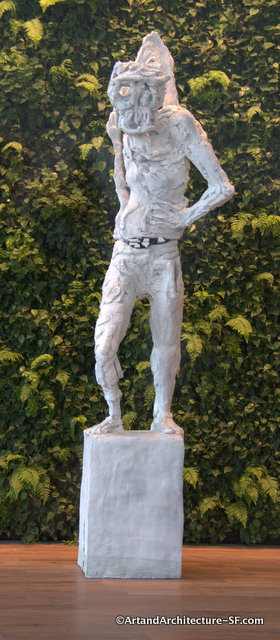

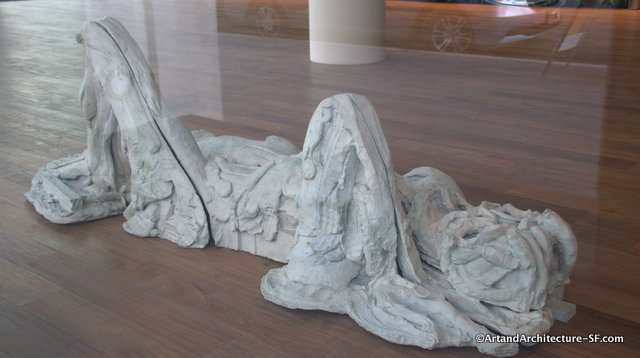

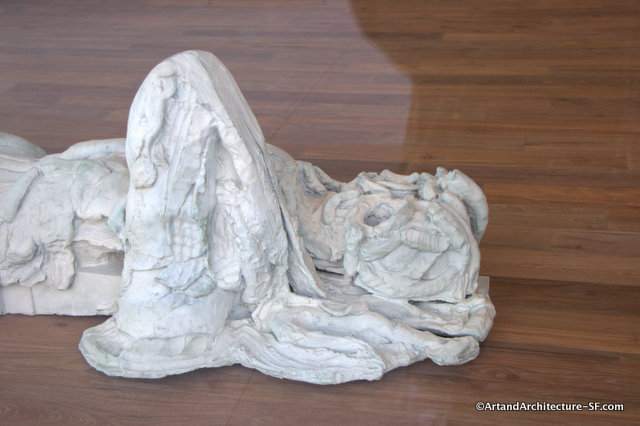

These two sculptures are by Thomas Houseago. The standing is titled Boy III and the one laying is Sleeping Boy. These are both white coated bronze.

Photo Courtesy of the San Francisco Planning Commission

Photo Courtesy of the San Francisco Planning Commission

This information about the artist comes from the San Francisco Planning Commission.

Thomas Houseago was born in Leeds, England in 1972. In 1989 he received a grant to attend a local art school called the Jacob Kramer Foundation College, and later continued his studies at Central St. Martin’s College of Art in London. After finishing college in London, Houseago attended De Ateliers in Amsterdam, after which he worked in Brussels for several years until 2004 when he moved to Los Angeles with his wife Amy Bessone.

Although Houseago had previously shown his work in Europe, his art has gone largely unrecognized in the United States until 2007 when a collector from Miami purchased eights of his sculptures. In 2008, Houseago had his first solo show in the United States titled Serpent, at the Los Angeles based David Kordansky Gallery. Houseago was inspired for that showing by Virgil’s The Aeneid and the Hellenistic masterwork Laocoon and His Sons.

Thomas Houseago draws inspiration for his art from the past, in particular the myths of Ancient Greece. He portrays the human body with the abstraction of the modern era, while rejecting the late-modernist notion of the purity of materials. His intense and impatient personality is reflected in his art, which tends to be rough and crude at times. Houseago is drawn towards materials like plaster because of his ability to heap it on to his sculptures with little precision. These particular works, Boy III and Sleeping Boy, are cast bronze with a white patina finish, a new medium for Houseago.

Thomas Houseago’s sculptures advance a psychological hold over their viewers through a highly evolved artistic language that embodies multiple contradictions: his works are simultaneously three dimensional and flat; sculpture and drawing; sharply angular and bulbous. They exude menacing strength whilst at the same time conveying vulnerability. Their rough surfaced forms seem inchoate, yet sophisticated, to be strangely autonomous: they are empty and yet alive.

Houseago has described himself as a realist. His concern, more than with the appearance of his sculptures, is to impart a sense of anima into the works: “As a sculptor, I am trying to put thought and energy into an inert material and give it truth and form” he has said. His sculptures reject the ironic re-workings of readymade vocabularies so prevalent in contemporary art in favor of a deeply individual reckoning with matter. His influences are the heavyweight sculptors of Western art— Picasso, Brancusi, Rodin, Moore and Michaelangelo can all be felt in his art, but his work equally draws from the everyday art forms of music, cartoons and movies: “I see Modernist art through the lens of pop culture, not the other way around.”

The process of making is extremely evident in Houseago’s sculptures. Materials such as plaster, iron rebar, hemp fiber and un- treated wood exert a raw physicality, and their rough forms reveal the actions that have made them. In Sleeping Boy and Boy III, bronze sculptures that arrest the plasticity of clay, the molding process has left each body part riven, with no attempt made by the artist to smooth over the joins or to fill in the hollows of their forms. Houseago’s sculpture is wantonly unrefined. His limbs emphasize their fragmentation rather than the humanist concerns of his art historical forbearers. In both works, Houseago draws broadly on Classical sculpture, seeing them through his own, unique vision. Boy III reaches back through time to refer to the kouroi, the proto-classical representations of male youths that emerged in ancient Greece. But the pose of Houseago’s youngster is informed less by those Archaic Period sculptures than the struts of fashion and pornographic photography, one arm looped behind the head, the other jutting so that its hand is on a hip.

Sleeping Boy by Thomas Houseago at StormKing

Sleeping Boy by Thomas Houseago at StormKing

The Financial Times did a very detailed article about Houseago and his creative process with some very informative photographs. You can read the article here.

Photo Courtesy of San Francisco Planning Commission

Photo Courtesy of San Francisco Planning Commission

The two planted walls behind the sculptures at Foundry Square are 27 feet in height. One of the walls is “hedge-like” while the other is a multitude of different colored leafage. The firm of SWA is the landscape architect. “The original idea was to consolidate the open space for all four buildings in a single plaza. The four corner bosques soften the intersection and create open space.”